In 2018 CRL commissioned a report assessing the effectiveness of current efforts to archive open web content as source materials for international and area studies (IAS) research, focusing specifically on the Caribbean and Latin America. While the web is now a key delivery medium for news, data, and contemporary discourse, the ephemerality of web content—the result of deletion, migration, alteration, or adulteration, collectively known as “reference rot”—has led to a crisis in scholarly communications. Conducting, sharing, and reading research based on open web sources is “like trying to stand on quicksand,” Harvard historian Jill Lepore noted in 2015.1 While issues of preserving and citing content that is published in online scholarly journals have largely been resolved, the accessibility and citability of fugitive source materials existing on the open web remain a problem.2

This article—the first of two highlighting aspects of the CRL report—examines systemic and region-specific issues arising from proliferating web content in Latin America, demonstrating challenges encountered in both real and hypothetical research examples.

Latin America Takes to the Web

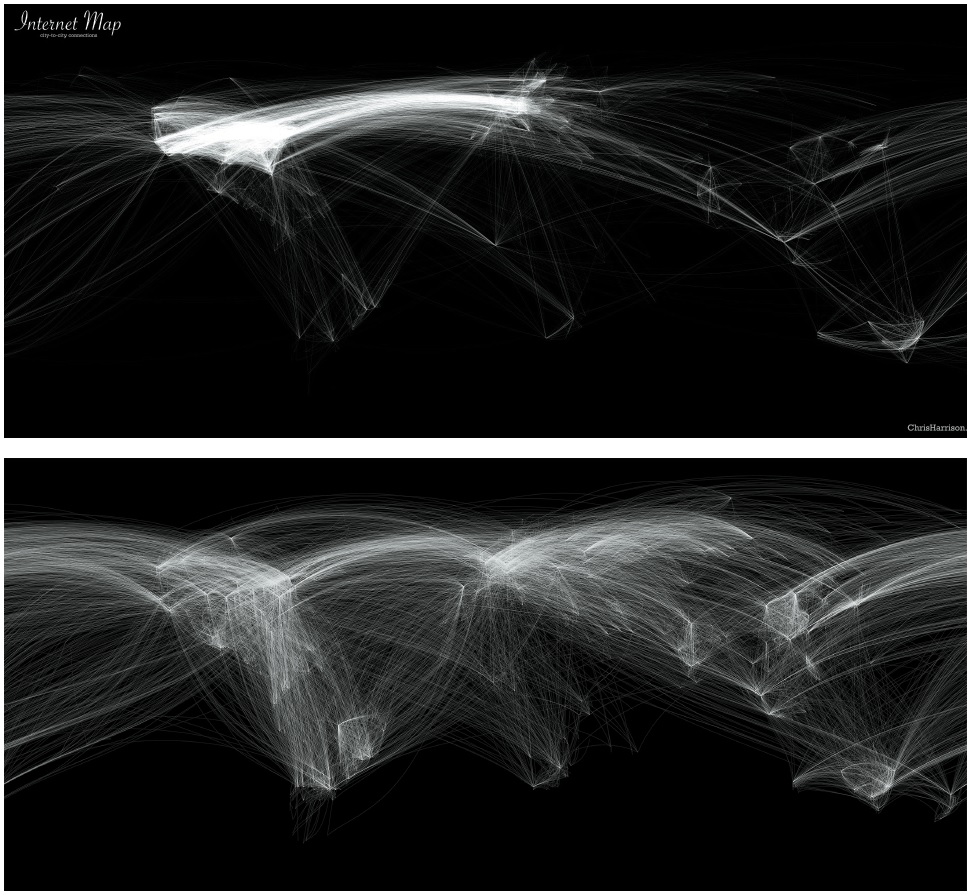

After a slow start in the 1990s and early 2000s, internet use in Latin America and the Caribbean exploded a little over ten years ago, and now exceeds that of the United States and Canada.3 The first image below shows city-to-city internet connections between North America, Europe, Africa, and South America in 2007. The graphic beneath it, created in 2011 using the same mapping algorithm, reflects the density of internet connections just four years later. Quite suddenly, South America and the Caribbean appear “on the map” as participants in world internet traffic, vastly outpacing Africa, though still lagging behind Asia’s even more explosive growth.4

Use of open web content, consisting of commercial, political, cultural, and scholarly websites, as well as the accessible subset of social media interchange, blogs, discussion forums, and much else, makes up a large portion of internet traffic—in Latin America perhaps even more than in North America, since, as Pamela Graham and Kent Norsworthy point out, “much digital publishing [in Latin America] is not channeled or distributed through traditional publishers but is instead only taking place on the freely accessible web.”5 To an extent even greater than in other parts of the world, the web in Latin America and the Caribbean is rapidly becoming the primary venue for information generated by the news media, governments, NGOs, and cultural organizations—in other words, the type of information that has traditionally provided the basis for the historical record. There can, therefore, be no doubt that the capture and archival preservation of web content from Latin America and the Caribbean is of great importance to students and scholars of this world region—even while harvesting and harnessing this content for scholarly use is still in its infancy, and faces particular challenges.

Unfortunately, preserving web content in Latin America has been especially slow getting off the ground. Some of the reasons are inherent to the web itself, while others are specific to Latin America and its history. On the systemic side, first, there is the inherent ephemerality of the medium: new content constantly overwrites the old, leaving not a trace of what had been there before.6 Second, there is still a prejudice held by many that content on the web has no heft, that it is more akin to idle conversation than content that merits preservation. For centuries this perceived lack of archival “worthiness” has made ephemeral formats—pamphlets, posters, playbills, newspapers—a lower priority for library preservation, despite the role ephemera have played in documenting, even precipitating, momentous events of history.

Third and finally, on the systemic side ethical concerns stand in the way of the preservation of much currently relevant web content, especially social media. These concerns become even more acute for web content in the human rights domain,where personal data regarding victims, informants, and perpetrators may become exposed to public view in a way paper archives cannot be. The attendant moral, legal, and political issues are aggravated by the globally perceived sense, underscored by news almost every day, that big American tech firms are predatory data gatherers, unconcerned with personal privacy and safety. Such concerns could easily scare off many smaller institutional players both here and abroad whose collective efforts to collect web-based text and data in Latin America and the Caribbean are essential, but are becoming more complicated—legally, ethically, and logistically—than ever before.

Then there are several specifically Latin American issues standing in the way of web content preservation. One is the absence of a strong archival tradition, in large part a legacy of centuries of colonial rule. For the Spanish-speaking countries in the Western hemisphere, archives and other important records were maintained for centuries not in-country, but instead at the seat of colonial power in Spain, consolidated in the 18th century in Seville, at the Archivo General de Indias.7 Perhaps this lack of inherited archival institutions contributes to the fact that to date, only a single Latin American country, Chile, has joined the International Internet Preservation Consortium (IIPC).8

Also painfully relevant is Latin America’s history of autocratic and dictatorial rule—relevant because the culture of autocracy, for many reasons, is hostile to memory institutions such as archives and libraries. The fact that erasure of the recent past is so easy on the web is a gift to rulers seeking to eradicate the memory of their predecessors or, perhaps, information reflecting poorly on their own regimes. To offer just one example: when the Honduran military overthrew the elected government of Manuel Zelaya in June 2009, the entire content of its web presence—speeches, government plans and reports, and details about the administration’s achievements—was summarily deleted as well.9

In Latin America, as elsewhere, valuable websites can also be hijacked by hostile commercial or political actors. For example, beginning sometime in the last few years and lasting until recently, visitors to cipamericas.org, the website of the Center for International Policy’s Americas Program based in Mexico City, found themselves redirected to a website offering cannabis derivative products. Faced with this problem, the parent organization, based in Washington, DC, decided to migrate to a new domain, americas.org, where all their “archived” content can once again be found. The move to americas.org solved one problem but has caused others, since until 2007 americas.org was the online home of the (now defunct) Resource Center of the Americas in Minneapolis, and later its successor, La Conexión de las Américas. Live web links to their content are now broken, too: the only access is through the Internet Archive.10

An inability or disinclination to rely on durable web infrastructure can also affect sustainable access for Latin American and Caribbean studies. Research on Cuban literature, for example, cannot overlook that much new work is circulated online, via blogs and webzines, and is backed up by individual readers only on “flash drives, kindles, etc. (and even, sometimes, in hard copy) before, during, and after circulation online.”11 Recognizing how fragile this distribution infrastructure is, individual scholars in the United States, as well as other countries, have used personal websites to store some of Cuba’s literary production and to share it on the web.12 These are by no means comprehensive, much less durable “archives.”

It is, however, both inaccurate and unfair to single out the Latin American web as somehow unique for link rot, content drift and loss, hijacking, and other forms of website abuse and manipulation. In fact, some forms of content loss encountered elsewhere in the world have not occurred in Latin America and the Caribbean. For example, the loss of entire nation-state domains—called ccTLDs, or country-code top-level domains—when countries cease to exist, has not occurred in the region as it did in multiple cases in Eastern Europe during the 1990s.13

Conducting Research in the Live and the Past Web of Latin America: A Hypothetical Example

To further illustrate the challenges facing researchers using web archives for this region, one might posit a scholar researching policies of the Dilma Rousseff presidency in Brazil affecting the Landless Workers Movement (MST), an important social movement in Brazil and elsewhere for the implementation of agrarian land reform. This scholar begins by looking for ideas and prospective primary sources, some of which will be on the web. She begins with broad scans in omnibus databases, such as Google, Google Scholar, Google Books, JSTOR, ProQuest Global Dissertations, and others. She discovers an intriguing master’s thesis by Maria A. Chavez of the University of Kansas entitled “Não é apenas sobre nós: Food as a Mechanism to Address Social and Environmental Injustices in Mato Grosso, Brazil.” There she finds references to a relevant policy document from 2014 bearing the title “Mais Mudanças, Mais Futuro” (“More change, more future”). The footnoted location of the original document, programadegoverno.dilma.com.br, no longer exists on the live web—an instance of link rot. What to do? She does succeed in finding the document— or at least a document bearing the same title—on the live web, but should she cite this location? She decides for two (good) reasons not to: for one, she doesn’t know if the document is identical to the original or might not have been redacted in the interim, e.g., at some point after the election or after Dilma Rousseff was impeached in 2016 (content drift).14 Second, she knows that there is no guarantee that a link to the live web will work over time to aid future researchers in reconstructing, reviewing, confirming, or challenging her findings. Our researcher then goes to the Library of Congress Web Archives, where she knows that there is a rich and publicly available archive for the 2010 presidential election in Brazil, but there is not currently an accessible collection created for the 2014 Brazilian election.15

Finally, she searches the Internet Archive using the original URL, and following one redirect, there it is: the page imbedding the policy document was crawled at 17:31:42 GMT on September 28, 2014—exactly one week before the Brazilian general election of October 5, 2014. She has her document, she believes, and it appears to have archival authority, and, based on the persistence policies of the Internet Archive, she can hope that it will also have a permanent location findable by later scholars. The only discomfiting fact is that the time-date-stamp of the PDF encoded in the archival URL is 15:26:48 GMT on October 15, 2014—ten days after the election—even though the crawl of the web page it is linked from is stamped September 28, 2014. So despite all her archival diligence, and the long path she has taken to obtain this version of the document, in the end our author still has no guarantee of her document’s authenticity. In the literature, this disparity is often called a time skew. The problem derives from the fact that an archived web page is not really a “snapshot” of a web page at all, at least not in the original photographic meaning of the word—as it is nonetheless frequently called among web archivists—but a “mixed display”: a composite reconstruction using crawls of different elements of a live web page undertaken at different times.16

Since the Internet Archive does all the crawls for Archive-It partners, among them the Library of Congress, Columbia, and the University of Texas, time skew is endemic to many web archives in the United States and Canada. This is, of course, a significant flaw in web archiving technology, at least from the perspective of researching historians.17 Perhaps this helps explain why so few researchers use archival versions of websites in published research, instead preferring to footnote a live website that may no longer exist or whose content may have changed (“drifted”) over time. Citing the original source may satisfy the scholarly requirement to document one’s sources, but in the new research environment of resources gathered on the open web, the practice often leaves the task to the reader to find—or not to find—the authentic, original content.

We live in a new documentary age when it comes to studying and reporting on the societies, politics, economies, and cultures of Latin America and the Caribbean. The fixity of past research material formats is gone, superseded by electronically produced and distributed source materials that morph or even disappear entirely before or after research based on them is shared. The following article looks closely at several large-scale preservation efforts in the United States to see how these programs approach the monumental task of capturing and preserving the evanescent forms information today often takes—and to see whether scholars are using these stable and preserved resources to document their work.

- Jill Lepore. “The Cobweb: Can the Internet Be Archived?” New Yorker, January 26, 2015. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/01/26/cobweb.

- See for example Rebecca B. Galemba. Contraband Corridor: Making a Living at the Mexico-Guatemala Border. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018. About 10% of the 102 links to open web content in this bibliography examined as part of the CRL study were no longer functioning by the time of its late 2017 release, including two to the now defunct cipamericas.org address (p. 265).

- According to the monitoring site Internet World Stats, of 4.2 billion internet users in the world (as of June 30, 2018, 10.4% reside in Latin America and the Caribbean, while 8.2% are in North America. Enrique de Argaez. “Internet World Stats: Usage and Population Statistics.” https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm.

- Images by Chris Harrison of the Human-Computer Interaction Institute at Carnegie Mellon University. Chris Harrison. “Internet Maps.” http://www.chrisharrison.net/index.php/Visualizations/InternetMap and personal communication.

- Pamela M. Graham and Kent Norsworthy. “Archiving the Latin American Web: A Call to Action.” In Latin American Collection Concepts: Essays on Libraries, Collaborations and New Approaches, edited by Gayle Williams and Jana Krentz. Jefferson, 224–236. N.C.: McFarland, 2019.

- Tim Berners-Lee, who developed the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP), the core DNA of the modern-day internet, is regretful today that he neglected to build memory—a time axis—into his invention. As he confessed to Lepore in an interview: “I was trying to get it to go. Preservation was not a priority.” (Lepore, 2015)

- http://www.mecd.gob.es/cultura/areas/archivos/mc/archivos/agi/presentacion/historia.html.

- See http://netpreserve.org/about-us/members/ for a map showing the worldwide distribution of IIPC members.

- For more on politically motivated website disappearances in Latin America—including the fate of the Zelaya government pages and the Zelaya administration’s post-coup afterlife as a website—see Kent Norsworthy. “Web Archiving and Mainstreaming Special Collections: The Case of the Latin American Government Documents Archive.” In The Signal, interviewed by Trevor Owens. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 2012.

- Graham Stinnett. “Rebel Collectors: Human Rights and Archives in Central America and the Human Rights Commission of El Salvador and the Resource Center of the Americas, 1978–2007.” Thesis, University of Manitoba/University of Winnipeg, 2010. A photo illustration from the current site of americas.org introduces this issue.

- Emily A. Maguire. “Islands in the Slipstream: Diasporic Allegories in Cuban Science Fiction since the Special Period.” In Latin American Science Fiction: Theory and Practice, edited by M. Elizabeth Ginway and J. Andrew Brown, 19–34. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. Also personal communication.

- For example, there is an archive of the Cuban SF magazine Disparo en Red at the University of South Florida, see http://digital.lib.usf.edu/disparo. Upper levels of this site have been crawled (and are preserved) by the Internet Archive, but individual issues of this magazine (active between 2004 and 2008) are not.

- Anat Ben-David. “What Does the Web Remember of Its Deleted Past? An Archival Reconstruction of the Former Yugoslav Top-Level Domain.” New Media & Society 18, no. 7 (2016): 1103-19.

- In fact, she cannot know for sure whether the document Chavez downloaded on November 16, 2014, was the same document as was on the site before the election over a month before.

- According to Library of Congress, LC did indeed crawl and archive the 2014 election in Brazil: as of this writing it was planned to be mounted as a collection in the near future.

- Gordon Mohr. “Wayback Machine & Web Archiving Open Thread, September 2010 “ In Web Archiving at archive.org, edited by Internet Archive Web Team: Internet Archive, 2010.

- Susanne Belovari. “Historians and Web Archives.” Archivaria: The Journal of the Association of Canadian Archivists, no. 83 (Spring 2017, 2017): 59–79.