The year 2013 marked the centennial of the opening of the Los Angeles Aqueduct in November 1913. The Special Collections Library at the University of California, Los Angeles, initiated the Los Angeles Aqueduct Digital Platform project (LAADP) to digitize the archives that document the development and construction of the aqueduct system, one of the largest engineering projects of the twentieth century. Christian Reed’s contribution to the commemorative project has received the 2014 CRL Primary Source Award for Research.

Reed, a Ph.D. candidate in English and a scholar at the Center for Primary Research and Training, was asked to use primary source materials to develop opportunities for the community to access and explore the LAADP, to encourage and engage community input, and to promote participation in commemorative activities. Jasmine Jones, the LAADP Project Manager, reports that Reed’s innovation “transcended the digital bounds of the LAADP” and brought together an “audience of diverse interests” that included environmentalists, academics, students, poets, artists, and others.

Reed based his project on the sonnet: a 14-line poetic form designed to express a single, complete thought, idea, or sentiment in one of a number of rhyming schemes, which concludes in a two-line couplet. As a poetry enthusiast and experienced teacher, Reed recognized that the sonnet form is uniquely suited to comparing and reconciling relationships that involve a power imbalance. In his research on the aqueduct system, Reed realized that the capability could be instrumental in helping to reconcile the competing viewpoints that envelop the aqueduct engineering project, which diverts water resources from rural Inyo County, adjacent to the Nevada border, 233 miles across the state to Los Angeles.

The Aqueduct, in Fourteen Lines

By David Ulin

Was the aqueduct built for orange juice?

You know what I’m saying Owens Valley

water irrigating breakfast concentrate,

two hundred fifty miles to the south.

Or was it built so William Mulholland

could ride out his last days awash in guilt

swept under the devastation wrought

by the collapse of the St. Francis dam?

Mulholland’s home was later laid waste for

a freeway, fitting, given the ghosts who

still haunt his penthouse office downtown. But

Los Angeles will have what it will have.

Which is? A future that works as we say

it does—and not the other way around.

For his experiment, Reid enlisted artists and activists, as well as UCLA faculty and students. This network included members with close ties to Owens Valley in Inyo County, individuals who were intimately involved in water rights research and activism, and others with no knowledge of the aqueduct system at all. To moderate the opposing views on the aqueduct system, Reed noted that “the sonnet performs this feat of thought by dissolving the unbalanced relationship into a linked series of problems. Each problem, together with its resolution, makes up a single sonnet that [link] into a structure called a sonnet cycle, an unfolding study of a single complex situation.”

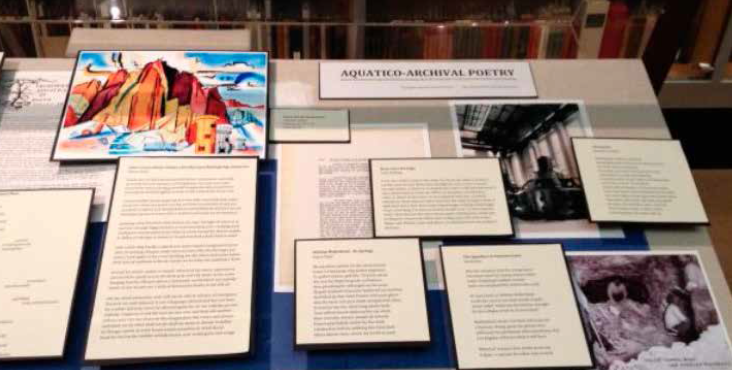

Using the sonnet as a communication device to encourage community input, Reed furnished participants with “raw sonnets,” composed of four primary-source archival elements (newspaper clippings, postcards, photos, and a draft script) and encouraged them to complete the poems based on their own interests. The diverse network of sonneteers produced numerous works that were presented in various ways: digital postings on the LAADP online platform; community-based café-style poetry readings with commentary from a distinguished UCLA English professor; and a physical presentation of the sonnets and the primary sources that inspired them, curated into a traditional exhibition and displayed in the Special Collections Library.